The online South African Rock Encyclopedia covers the history of South African rock music from the 1950s up to the early 2000s. All this information is made freely available to the public.

Home > Rock Legends > 1970s > Otis Waygood

Biography | Discography | Reviews

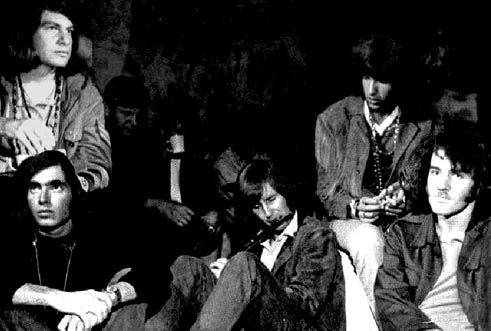

Otis Waygood

It was the worst of times in Joburg's white suburbs. The Beatles were banned on state radio. Haircut regulations were merciless. The closest thing to a pop star was Gê Korsten. Life was an unutterable hell of boredom and conformity, but lo: salvation awaited. They came from the north in the summer of '69, armed with axes and Scarabs, long hair streaming behind them, and proceeded to slay the youth of the nation with an arsenal of murderous blues-rock tunes, synchronized foot-stomping and, on a good night, eye-popping displays of maniacal writhing in advanced states of rock 'n' roll transfiguration. The masses roared. The establishment was shaken. They were the biggest thing our small world had ever seen, our Led Zeppelin, our Black Sabbath, maybe even our Rolling Stones. They were the Otis Waygood Blues Band, and this is their story.

It begins in 1964 or so, at a Jewish youth camp in what was then Rhodesia. Rob and Alan Zipper were from Bulawayo, where their dad had a clothes shop. Ivor Rubenstein was Alan's best mate, and Leigh Sagar was the local butcher's son. All these boys were budding musicians. Alan and Ivor had a little "Fenders and footsteps" band that played Shadows covers at talent competitions, and Rob was into folk. They considered themselves pretty cool until they met Benny Miller, who was all of 16 and sported such unheard-of trappings as a denim jacket and Beatles-length hair. Benny had an older sister who'd introduced him to some way-out music, and when he picked up his guitar, the Bulawayo boys were staggered: he was playing the blues, making that axe sing and cry like a negro.

How did the music of black American pain and sufferation find its way to the rebel colony of Rhodesia, where Ian Smith was about to declare UDI in the hope of preserving white supremacy for another five hundred years? It's a long story, and it begins in Chicago in the forties and fifties, where blues cats like Howlin' Wolf and Sonny Boy Williamson cut '78s that eventually found their way into the hands of young British enthusiasts like John Mayall and Eric Clapton, who covered the songs in their early sessions and always cited the bluesmen as their gurus. Word of this eventually penetrated Rhodesia, and sent Benny scrambling after the real stuff, which he found on Pye Records' Blues Series, volumes one through six. Which is how Benny Miller came to be playing the blues around a campfire in Africa, bending and stretching those sad notes like a veteran. The Bulawayo contingent reached for their own guitars, and thus began a band that evolved over several years into Otis Waygood.

In its earliest incarnation, the band was built around Benny Miller, who remains, says Rob Zipper, "one of the best guitarists I've ever heard." Rob himself sang, played the blues harp and sax. His younger brother Alan was on bass. Bulawayo homeboys Ivor and Leigh were on drums and rhythm respectively, and flautist Martin Jackson completed the lineup. Their manager, Andy Vaughan, was the dude who observed that if you scrambled the name of a famous lift manufacturer you came up with a monniker that sounded authentically American negro: Otis Waygood. Rob thought it was pretty witty. Ivor said, "Ja, and lifts can be pretty heavy too." And so the Otis Waygood Blues Band came into being.

By now, it was 1969, and the older cats were students at the University College of Rhodesia, earnest young men, seriously involved in the struggle against bigotry, prejudice and short hair. By day they were student activists, by night they played sessions. Their repetoire consisted of blues standards and James Brown grooves, and they were getting better and better. They landed a Saturday afternoon gig at Les Discotheque. Crowds started coming. When Rob stood up to talk at student meetings, he was drowned out by cries of, "You're Late Miss Kate."

"Miss Kate" was the band's signature tune, an old Deefore/Hitzfield number that they played at a bone-crunching volume and frantic pace. Towards the end of '69, Otis were asked to perform"Miss Kate" on state TV. The boys obliged with a display of sneering insolence and hip-thrusting sexuality that provoked indignation from your average Rhodesian. These chaps are outrageous, they cried. They have "golliwog hair" and bad manners! They go into the locations and play for natives! They aren't proper Rhodies!

Indeed they weren't, which is why they were planning to leave the country as soon as they could. Rob graduated at the end of 1969, and he was supposed to be the first to go, but it was summer and the boys were young and wild and someone came up with the idea of driving to Cape Town. Benny Miller thought it was a blind move, and refused to come. But rest were bok, so they loaded their amps into a battered old Kombi and set off across Africa to seek their fortune.

South of the Limpopo River, they entered a country in which a minor social revolution was brewing. In the West, the hippie movement had already peaked, but South Africa was always a few years behind the times, and this was our summer of love. Communes were springing up in the white suburbs. Acid had made its debut. Cape Town's Green Point Stadium was a great milling of stoned longhairs, come to attend an event billed as "the largest pop festival south of and since the Isle of Wight." It was also a competition, with the winner in line for a three-month residency at a local hotel. Otis Waygood arrived too late to compete, but impresario Selwyn Miller gave them a 15-minute slot as consolation -- 2pm on a burning December afternoon.

The audience was half asleep when they took the stage. Twelve bars into the set, they were on their feet. By the end of the first song, they were "freaking out," according to reports in the next morning's papers. By the time the band got around to "Fever," fans were attacking the security fence, and Rob got so carried away that he leapt off the ten-foot-high stage and almost killed himself. "That's when it all started," he says. Otis made the next day's papers in a very big way, and went on to become the "underground" sensation of 1969's Christmas holiday season, drawing sell-out crowds wherever they played.

In South Africa, this was the big time, and it lasted barely three weeks. The holidays ended, the tourists departed, and that was that: the rock heroes had to pack their gear and go back home. As fate would have it, however, their Kombi broke down in Johannesburg, and they wound up gigging at a club called Electric Circus to raise money for a valve job. One night, after a particularly sweaty set, a slender blonde guy came backstage and said, "I'm going to turn you into the biggest thing South Africa has ever seen."

This was Clive Calder, who went on to become a rock billionaire, owner of the world's largest independent music company. Back then he was a lightie of 24, just starting out in the record business. His rap was inspirational. Said he'd just returned from Europe, where he'd seen how the moguls broke Grand Funk Railroad. Maintained he was capable of doing the same thing with Otis Waygood, and that together, they would conquer the planet. The white bluesboys signed on the dotted line, and Clive Calder's career began.

The album you're holding in your hand was recorded over two days in Joburg's EMI studios in March, 1970, with Calder producing and playing piano on several tracks. Laid down in haste on an old four-track machine, it is less a work of art than a talisman to transport you back to sweaty little clubs in the early days of Otis Waygood's reign as South Africa's premier live group. Rob would brace himself in a splay-legged rock hero stance, tilt his head sideways, close his eyes and bellow as if his life depended on it. As the spirit took them, the sidemen would break into this frenzied bowing motion, bending double over their guitars on every beat, like a row of longhaired rabbis dovening madly at some blues-rock shrine. By the time they got to "Fever," with its electrifying climactic footstomp, the audience was pulverized. "It was like having your senses worked over with a baseball bat," said one critic.

Critics were somewhat less taken with the untitled LP's blank black cover. "We were copying the Beatles," explains Alan Zipper. "They'd just done The White Album, so we thought we'd do a black album." It was released in May 1970, and Calder immediately put Otis Waygood on the road to back it. His plan was to broaden the band's fan base to the point where kids in the smallest town were clamouring for the record, and that meant playing everywhere - Kroonstad, Klerksdorp, Witbank, you name it; towns where longhairs had never been seen before.

"In those smaller towns we were like aliens from outer space," says drummer Ivor. "I remember driving into places with a motorcycle cop in front and another behind, just sort of forewarning the town, 'Here they come.'" Intrigued by Calder's masterful hype campaign, platteland people turned out in droves to see the longhaired weirdos. "It was amazing," says Ivor. "Calder had the journalists eating out of his hand. Everything you opened was just Otis."

The boys in the band were pretty straight when they arrived in South Africa, but youths everywhere were storming heaven on hallucinogenics, and pretty soon, Otis Waygood was doing it too. By now they were living in an old house in the suburbs of Jo'burg, a sort of head quarters with mattresses strewn across the bare floors and a family of 20 hippies sitting down for communal meals. The acid metaphyisicians of Abstract Truth crashed out there for weeks on end. Freedom's Children were regular guests, along with African stars like Kippie Moeketsi and Julian Bahula. Everyone would get high and jam in the soundproofed garage. Otis' music began to evolve in a direction presaged by the three bonus tracks that conclude this album. The riffs grew darker and heavier. Elements of free jazz and white noise crept in. Songs like "You Can Do (Part I)" were eerie, unnerving excursions into regions of the psyche where only the brave dared tread. Flautist Martin Jackson made the trip once too often, suffered a "spiritual crisis" and quit the band.

His replacement was Harry Poulos, the pale Greek god of keyboards, recruited from the ruins of Freedom's Children. Harry was a useful guy to have around in several respects, an enormously talented musician and a Zen mechanic to boot, capable of diagnosing the ailments of the band's worn-out Kombi just by remaining silent and centred and meditating on the problem until a solution revealed itself. With his help, the band recorded two more albums in quick succession ('Simply Otis Waygood' and 'Ten Light Claps and a Scream') and continued its epic trek through platteland towns, coastal resorts and open-air festivals. They finished 1970 where they started - special guests at the grand final of Cape Town's annual Battle of the Bands. The audience wouldn't let them off the stage. Rob worked himself into such a state of James Brownian exhaustion that he had to be carried off in the end. "Whether you accept it or not," wrote critic Peter Feldman, "1970 was their year."

After that, it was all downhill in a way. There were only so many heads in South Africa, and by the end of 1970, they'd all bought an Otis LP and seen the band live several times. Beyond a certain point, Otis could only go round in circles. Worse yet, conservatives were growing intolerant of long-haired social deviance. National Party MPs complained that rock music was rotting the nation's moral fibre. Right-wing students invaded a pop festival where Otis was playing and gave several particants an involuntary haircut. "We had police coming to the house every second night," says Ivor, "or guys with crewcuts and denim jackets saying, 'Hey, man, the car's broken down, can we sleep here?' They always planted weed in the toilets, but we always found it before they bust us."

By March, 1971, the day of was drawing nigh. Describing drug abuse as a "national emergency," the Minister of Police announced a crackdown. At the same time, various armies started breathing down Otis Waygood's neck. When the SADF informed Ivor that he was liable for military service, the boys sneaked back into Rhodesia, but more call-up papers were waiting for them at their parents' homes. "Ian Smith despised us," says Ivor. "They wanted to make an example of us, so we basically escaped." At the time, international airlines weren't supposed to land in Rhodesia because of sanctions. But there was a Jo'burg-Paris flight that made a secret stop in Salisbury. The boys boarded it and vanished.

Back in Jo'burg, we were bereft. Friends and I started a tribute band that played garage parties in the white suburbs, our every lick, pose and song copied off Otis, but that petered out in a year or two, and we were left with nothing but their records and vague rumours from a distant hemisphere. Otis were alive and well in Amsterdam. Later, they were spotted in England, transmogrified into a white reggae band that played the deeply underground blacks-only heavy dub circuit. Later still, they became Immigrant, a multi-racial outfit that did a few gigs at the Rock Garden and the Palladium. But it never quite came together again, and the band disintegrated at the end of the seventies.

Today, Leigh Sagar is a barrister in London. Rob Zipper practices architecture. Alan Zipper runs a recording studio. Ivor Rubenstein returned to Bulawayo, where he manufactures hats. Clive Calder is chairman of Jive Records and ruling genius of the teen pop genre, responsible inter alia for the Backstreet Boys and Britney Spears. Martin Jackson was last seen drifting around Salisbury with a huge cross painted on his back, and is rumoured to have died in the mid-seventies. Harry Poulos stepped off a building, another casualty of an era whose mad intensity made a reversion to the ordinary unbearable.

As for Benny Miller, the guy who started it all, he's still in Harare, wryly amused by the extraordinary adventure he missed by ducking out of that fateful trip to Cape Town. He still plays guitar in sixties nostalgia bands, and produces African music for a living.

See also the Sleeve Notes for "Ten Light Claps And A Scream" CD re-issue in 2010.

Otis Waygood Band

A review of the three known European 45's from 1977

by Bas Möllenkramer, Soest, the Netherlands

Bulawayo Boys The Band may have worked in Salisbury a lot, but they were from Bulawayo - they all went to Milton School, where one of the early bands formed by the Zipper Bros were known as "The Merseys". The Zipper family owned one of the town's high class clothing shops which was also known as Zippers.

Salisbury produced bands like Holy Black, etc but the Otis Waygood Band were Bulawayo's own.Keith Downs, November 2001

UPLIFTING MUSIC Oddly enough, after I listened to Otis Waygood [the recent CD re-issue from RetroFresh], I read some more in Ian Fleming's James Bond thriller 'Doctor No', and found a mention of a 'Waygood Otis' lift (in Doctor No's lair). Now, I had always thought the only part of their name that referred to elevators was the 'Otis' part -- maybe 'Otis', by itself, is the name of the American division of the company. I never heard of 'Waygood Otis', and I've been in plenty of elevators and have read in bronze 'Otis' overhead many times. The 'Waygood' part of the band's name I always took, reasonably and justifiably, to mean that they were better than good, that they were "way good, man." Anyway, I learned something about SA music from a James Bond book.

Kurt Shoemaker, Texas, June 2001