The online South African Rock Encyclopedia covers the history of South African rock music from the 1950s up to the early 2000s. All this information is made freely available to the public.

Home > Rock Legends > 1970s > Hawk > Discography > African Day

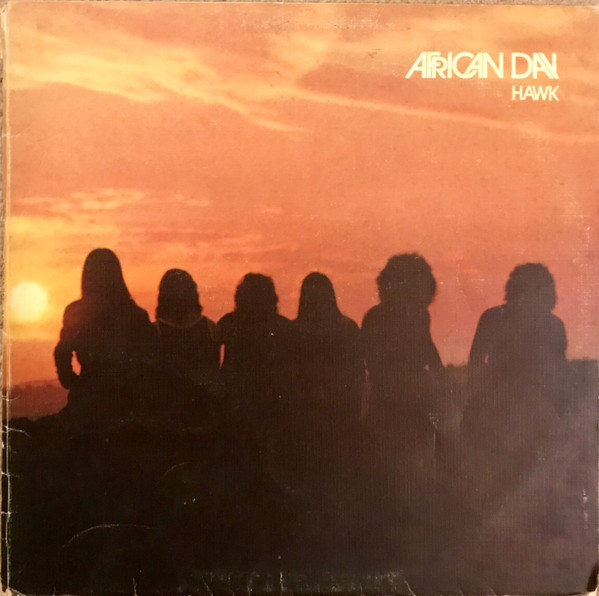

Hawk - African Day (1971)

Hawk - African Day (1971, Back cover)

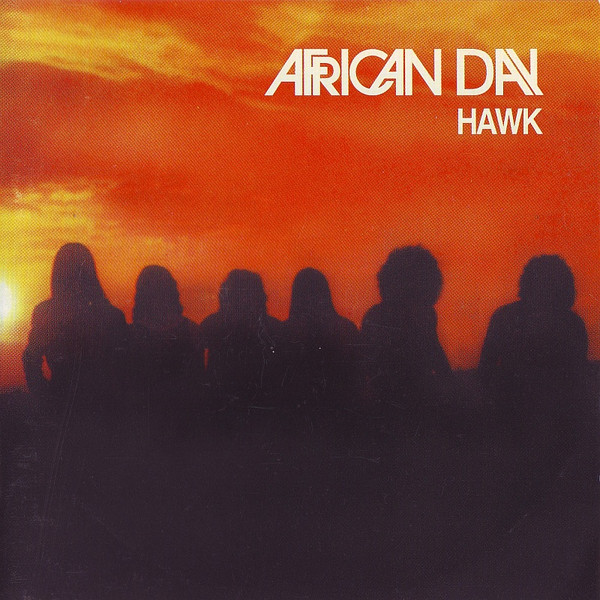

Hawk - African Day (2001 CD)

Bonus tracks on CD re-issue (previously unreleased live recordings from 10th June 1971):

Bonus tracks are incorrectly named on the CD back cover and on Spotify.

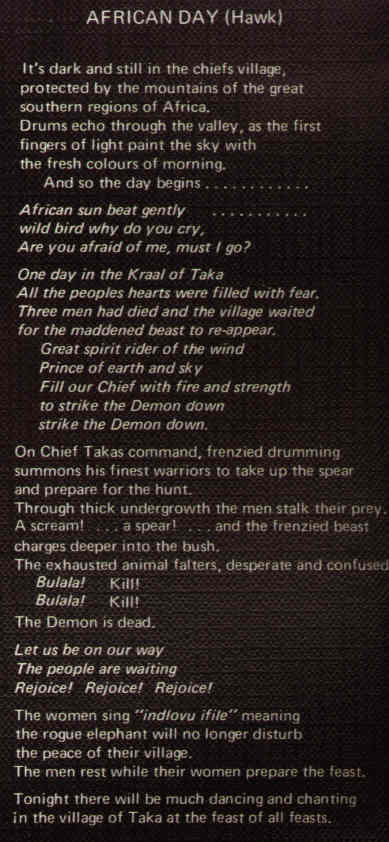

Hawk - African Day Lyrics

A Clive Calder production, engineered by Leo Lagerway & Jeremy George.

LP: 1971, EMI Parlophone, PCSJ (D) 12080

CD: 2nd April 2001, RetroFresh, freshcd 108

The African Day story

He's a good man, Dave Ornellas. But then he's always been good; rising like a colourful prophet of old from the smoking stage, with a voice Joe Cocker might have envied. Wild black hair and flowing beard, he chose – in the early years – the complex simplicity of making music the African way.

No, not fusion.

But earthy stuff – the virile, extraordinary, substance concept albums are made of.

Strange to write that now, thirty-something years on.

The "concept album", with its long, interwoven tracks, telling a musical story, was the avant-garde pop symphony of the 1970s. It is also long dead. Everyone did concept albums – Pink Floyd with Ummagumma, Genesis (the original Genesis, that is, when Phil Collins was a drummer, not a weasel-voiced vocalist) produced them with Trespass and Foxtrot (and at a push The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.) Deep Purple went even further, seconding the entire Royal Philharmonic and Malcolm Arnold in the Royal Albert Hall to do their seminal Concerto for Group and Orchestra and equally impressive, but not as melodic Gemini Suite. Add Uriah Heep and Free, who fringed – and Emerson, Lake and Palmer (and the Nice) who turned classical themes – like Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kije Suite– into mind-numbing extravaganzas, sometimes stabbing the keyboard with a knife to hold the note.

It was the rage of course, resurrecting itself from the post-World War 2 How Much Is That Doggie in the Window? Mocking Bird Hill syndrome; the hysterical – but musically brilliant – pop culture of The Beatles and the raunchy y'all R&B of the Rolling Stones. And who can forget The Who?

In Johannesburg, bursting, like Durban, with musicians aeons ahead of their time, Ornellas added the sunburnt, brown prairies of Africa to the genre of the concept album – the heady, steady beat of drums, and enough cross-rhythms to make you dizzy.

Add the mesmerising voices – and the telling story.

Tuck in the ranging flute, the saxophone. The deep bass buzz. And the mesmerising, talking drums.

African Day, all 17-plus minutes of it, was the birth of a home-grown concept later taken up by Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu, and the other rising sons of South African music.

"John used to sit at the foot of the stage with 'smoke' from the ice machine curling down, when we performed," says Ornellas. "He was about 15 years old – sometimes Sipho was with him. Sometimes they danced."

African Day took up the entire side one of the album of the same name, something never quite before seen, or heard, in a country alive with indigenous sounds no-one had worried to emulate, because the "culture" was foreign. In other words, not "white." And everyone knew, in a society insanely paranoid with Apartheid-speak, that only "white people" could, well, make music.

The others could develop separately.

Hawk changed – and challenged – that immediately.

In the off stage darkness a voice intoned:

It's dark and still in the chief's village protected by the mountains of the great southern regions of Africa ...

Drums echo through the village as the first fingers of light paint the sky with the fresh colours of morning, and so the days begins ...

And so, too, the lights came up. It was the prelude to a unique, colourful, performance, and once caught live, and the story dramatically revealed, was never forgotten.

It was music theatre on a grand, unique, stage.

One day in the Kraal of Taka,

All the peoples' hearts were filled with fear,

Three men had died and the village waited

For the maddened beast to re-appear.

An African story, this. Of a killer, rogue elephant, a rampaging, out of control beast. A story culled from the heat and dust of Africa, a fast-disappearing natural world around us. An avant garde tone poem.

Ornellas, diminutive now, with craggy face and short, off-black hair, sips orange juice. We are in the lounge of his Cape Town home, with his young son, Caleb. His dogs huff and puff in the heat.

At my feet, the instrument of his profession and his success – a guitar. New strings, in a box, lie on the table.

It is a good meeting.

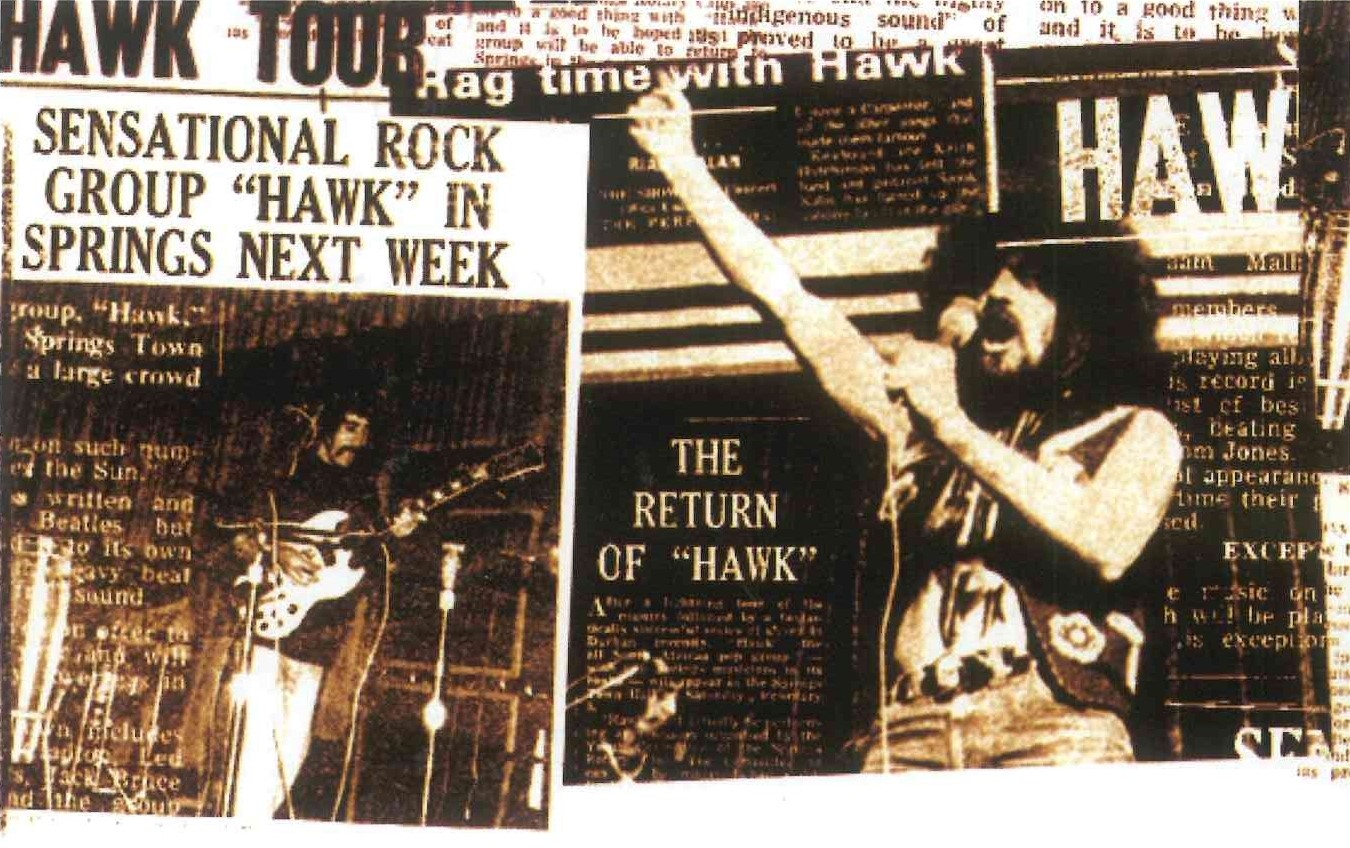

I last saw him around 1970-71 in Durban. Whatever the year, Hawk headlined at the Battle of the Bands – an annual bash put on by the music magazine I edited, Trend, and Durban councillor Peter Breytenbach, who organised the City Hall and the anti-riot-drug squad. It was a good year for music. On the show were Otis Waygood Blues Band, Abstract Truth, Scratby Hud, and a collection of good local bands. Voting was by four judges – I was not one, but my colleague Carl Coleman was.

Hawk, in full flight tore the house down with a storming set, a beaming Ornellas, dressed in flowing African-style full-length robes shaking the perspiration from his oval of deep black hair.

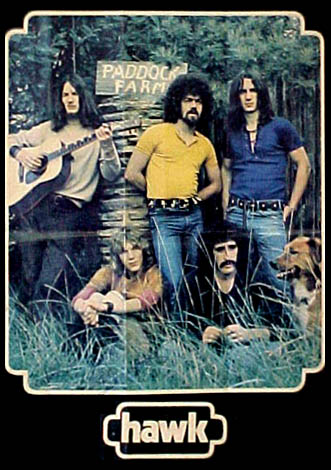

Hawk

Not bad for a lad who grew up in Cape Town's southern suburbs and went to Plumstead High School. And learned to play the acoustic guitar.

Ornellas says: "I wanted to go to university, but didn't make it. That was bad news, because I was pretty keen. Instead, in 1967, I headed north to Johannesburg and the school of mines. I wanted my future to be in the science of metallurgy, and eventually landed up on the Kloof gold mine."

It was dismal, and not what Ornellas wanted. But his next move was the nudge into an entirely new career.

"I went to art school – in the centre of the city. There I met a fellow student who was very neat on the guitar. His name was Mark Kahn – better known as 'Spook'. He could really play lead, while I tucked myself in on rhythm. Soon we a pretty tight duo and called ourselves The Buskers and got regular work at that music hangout, the Troubadour in Johannesburg."

Kahn says: "It was amazing how it all came together. This dude Ornellas could make things happen. Hey, it was a pretty exciting thing. We kind of rolled up at these places, you know. Kind of casing the scene. What we really wanted to do was play with some people – you know, people with drums and keyboard and sax – that kind of stuff."

Extraordinary things began to slot into place.

Ornellas believes in extraordinary things – like meeting "his hero" for the first time.

"It was Mike Dickman – he had been playing electric guitar with a group called Flood which also included Pete Measroch, Rod Clarke and Richard Johnson. Well, I spent hours listening to Mike, so laid back, so cool, so collected. The man was a guitar wizard. When he hit the strings, the wood talked."

Richard remembers "Flood was playing a weekly gig at the Troubadour. Dave and Spook would drop by to do a set or two and as most musos do we checked each other out. In the same block as the Troubadour Keith and Braam were playing in a group called Toad then as if by fate both bands folded virtually at the same time; Mike and Pete went on to Abstract Truth and I, together with Keith and Braam teamed up with Dave and Spook to form Hawk".

Spook says: "This coming together seemed some kind of destiny. Here were these fellows – just what we were looking for, Dave and I. I suppose we sniffed around for a while – they could hear what we could do; we could see what they could do.

"They went so far as to let us use their instruments, too.

"We found a togetherness, a synergy. And we found the farm."

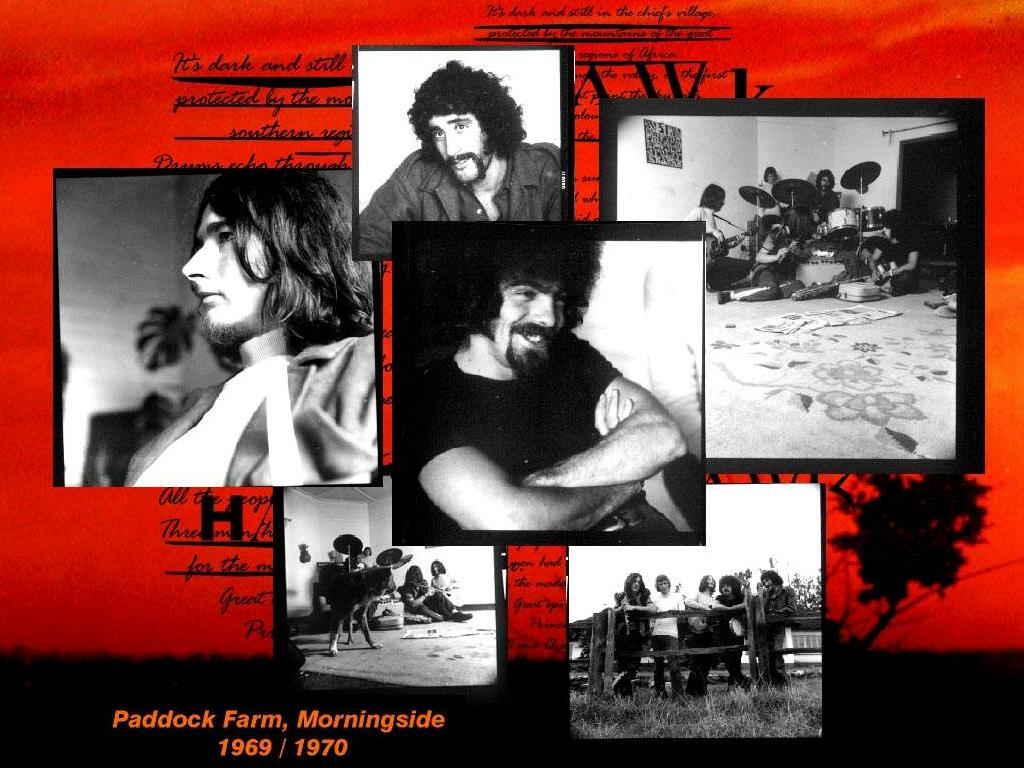

Paddock Farm, to be exact. In Morningside, Rivonia, on the outskirts of Johannesburg.

Paddock Farm 1969/1970

Says Ornellas: "We had no money; so we grew our own stuff – someone gave us a huge jar of mayonnaise once, and we ate it for weeks with home grown salads. We played the Troubadour; we played here and there. We wrote music. We did our own cover versions. And for a while had a female singer – Maureen England, who made a name for herself later in folk.

"And we called ourselves Hawk – after a hawk that lived on the farm. We were beginning to fly, and formulate the direction our music was going to take. We were listening to a lot of Hugh Tracey tapes – the expert Afro-musicologist who had travelled Africa placing sounds and music on tape for posterity.

"We went to Swaziland and came back with our own sounds, drums and a burning desire to make our own brand of African music. From all of this came African Day."

There is a touch of wistfullness as Ornellas says: "We told a story. It was a simple one. And we put everything into it – just listen to Keith's sax; the pain of the elephant is there.

"We produced a spectacle – spears on stage and the like."

It is an understatement of considerable proportions. Hawk's stage spectacular was a masterpiece of the time – not only on stage, but also in the huge, open-air concerts that became the rage of the 1970s, rain notwithstanding.

The real miracle was that no-one was electrocuted.

Spook says: "Sometimes I look back – I mean there we were, running around in leopard skins. Perhaps in hindsight it was just too pretentious. Too much. But it worked."

Richard says: "Here's something most people have already forgotten – when we went on stage, we were the first live group to have their own permanent sound engineers out there among the audience.

"One was Don Williamson, the other Trevor Pitout. We called him Snake – I don't think anyone ever called him Trevor. Anyway, there they were out there, at their huge sound desk. Now this was a major technological advance, because we had the most amazing sound equipment you could imagine.

"So much so that the British group Barclay James Harvest, who were here at the time, couldn't believe their ears. They had never heard anything like it. I was later tour manager with them – I know what they thought.

"Anyway, this gave Hawk a unique sound – like it was another dimension. It was raw. Vital stuff."

As is Johnson's bass, throughout the various movements of African Day.

With Hawk flying high, a manager had appeared on the scene – smart-talking Geoff Lonstein – and a record deal had been struck with EMI-Parlophone.

It was a dream come true.

But Lonstein caused problems.

Keith Hutchinson recalls: "I went to war with Lonstein. We were playing to packed houses everywhere. The show was massive. We were successful. People liked us. But we weren't getting what we deserved.

"Money came in, but not to us.

"There were times when I had to hitch from the farm to Highlands North because I didn't have money. Sometimes I walked – and that was pretty far. We came away with virtually nothing in our pockets.

"Then one day I'd had enough.

"We were in the middle of a rehearsal. I stopped it – That's it, guys, I said. No more. We are not going to do this any more. It's enough.

"Someone must have called Lonstein - half an hour later he arrived to try and sort it all out.

"For a while it seemed okay. But then three months later, I quit."

I hear this graduate of the Royal School of Music chuckle over the telephone: "One thing – I learned how to play a saxophone and flute. African Day was a good concept – it was fun at the time."

Apart from African Day, as the side one concept, Hawk began writing more tracks – Richard Johnson with Happy Man, Ornellas with Look Up Brother, Keith with Love Song, Ornellas and Spook with Kissed by the Sun – and an evocative cover version of George Harrison's Here Comes the Sun.

Look Up Brother, with its evocative solo acoustic lines, supplemented suddenly by a second guitar, and building up to a vocal climax, is one of the most beautiful songs penned.

Kissed by the Sun – "I wrote it in the swimming pool" says Ornellas, is another gem, with Spook providing the melody.

Another version of the song is included in this reissue of the album. It is one of four bonus live tracks recorded at a Concert for Hugh Tracey`s International Library of African Music on 10th June 1971, at the Selbourne Hall, in Johannesburg (courtesy of Dave Marks' 3rd Ear Music)

The other three tracks are a previously unrecorded African Rondo, a spectacular run through of The Hunt and another version of Look Up Brother.

Hawk

Ornellas says: "The album was simple really – kind of contemporary folk-rock. It came out, we were happy. Then Lonstein turned us into a multi-voiced, huge ensemble that destroyed the simplicity" – Ornellas uses that word often – "we had strived so hard for, and which had become part of us.

"It was a disappointment."

Kahn says: "The other day Richard and I were talking – we see quite a lot of each other. We kind of both came up with the same thought. Someone had been talking about Clive Calder and the major success he had become – he is perhaps the biggest record company executive in the United States today.

"Not bad for someone who had this little downtown Johannesburg office and a company called CCP – Clive Calder Productions. You remember – had artists like Richard John Smith?

"Well, Hawk at one time had this choice – either go with Lonstein, or sign with Calder.

"We went the wrong way. We signed with Lonstein. Someone said, Better the devil you know than ... well, you know the rest. What would have happened to us today? I guess it's a question that has no answer ..."

We talk briefly about another former South African, regarded today as perhaps the world's greatest record producer – the reclusive Robert John "Mutt" Lange.

But the talk is wishful.

Johnson just says: "Lonstein took the magic out of the band ..."

But Braam Malherbe talks of magic – and indeed without his drum work, African Day would not have been the barnstorming success it became.

He says: "They were magic years. This was jungle music."

But then Braam was brought up on the likes of John Bonham (Led Zeppelin) and Keith Moon (The Who). "I learned those solo pieces," he says, "I could play them. I'm a rock and roller.

"Jungle music is close to my heart – and no-one today can do it, other than musicians from the Congo. It's alive and well there. Colin Pratley (former drummer with Freedom's Children) feels the same way. He has that excitement too. It's in his work."

Malherbe adds another dimension, however, to the Hawk story.

"It was political, you know. I mean there's that elephant destroying things left, right and centre – driving people from their land. We were making a huge comparison – if anyone had analysed the words then, they'd have realised what we were on about.

"But when we played the small centres, people jeered and mocked us for wearing long hair, while they walked around in safari suits with combs stuck in their socks."

Braam says: "Perhaps the problem was that we didn't write hit parade stuff. It was far too complex and deep for that – hey, no DJ would play the entire album."

There is another consideration. Radio play was strictly monitored – words had to be supplied with the albums touted by recording company representatives, seeking air time. Too often records were banned.

Malherbe says: "I enjoyed that time. It was magic."

Ornellas says: "Suddenly, in 1972, we had that unsung giant of South African music, Ramsay MacKay with us. Les 'Jet' Goode, who had been playing with the British group Jericho, joined us in the place of Richard Johnson. The extraordinary Julian Laxton, who had been flirting with Freedom's Children and drummer Ivor Back was taken on.

"In a flash, we had a whole lot of Black musicians too – Alfred 'Ali' Lerefolo came in on African drums and vocals, as did Billy 'Knight' Mashigo, who also handled percussion. There was Audrey Motaung on vocals with Peter Kubheka."

Instead of a group, they had become a collective. A marketing proposition, with prospects of becoming a commercial giant. For Lonstein.

Richard remembers the split of the original lineup with a touch of sadness "This was heavy stuff. Both Braam and I lost our places in the band which had nothing to do with the music. It was the machinations and scheming of the management.

"Leaving the band in this way hurt really badly as we were a few weeks away from recording the second album."

Although the new lineup went on to record the Africa, She Too Can Cry album and toured Europe to critical acclaim the long awaited breakthrough failed to materialise and the group splintered in a blaze of publicity and recriminations but that, as they say, is another story sometime to be told.

The original band reformed a couple of years later.

But things had changed.

Today the Hawks are active in many fields:

Now, over thirty years later, the reissue of African Day stands as a testament to the collective magic of five musicians who drew inspiration from the red dust of Africa and created a musical epic that surely must rank with some of the greatest rock debut albums of all time.

Owen Coetzer, Cape Town, March 2001Dave Ornellas passed away on the 8th September 2010.

Owen Coetzer has been writing about music for 30 years. In the 1970s he ran a pop magazine in Durban called Trend. It was part of the then Daily News. He contributed to Music Maker magazine, which saw the light of day in Johannesburg in the late 70s and was their Cape Town correspondent. He ran regular music columns for the Argus and Weekend Argus, in full support of South African rock music. He is also a former chairman of the Natal Folk Music Association and played Sitar. He is now retired with his collection of CDs – The Who, the Rolling Stones and is currently taken with Pearl Jam and Jane's Addiction.

SA Rock Digest, April 2001

30 years later, the dawn rises on the long awaited reissue of Hawk's classic Afro rock masterpiece 'African Day'. It was officially released on Monday 2nd April (distributed by BMG) and has been digitally restored with four bonus live tracks from early 1971 as well as extended artwork incorporating fantastic liner notes by Owen Coetzer and many never-seen-before photos from the band's own archives.

RetroFresh, February 2001

Due out in March after nearly six months of planning is the band approved classic debut album by Hawk... "African Day". The album features all the original tracks, digitally remastered and includes four previously unreleased live tracks from 1971; "African Rondo", "Kissed by the sun", "The Hunt" and "Look up brother" (courtesy of David Marks and 3rd Ear Music). The extended artwork features rare photos, poster art and extensive liner notes by noted music journalist Owen Coetzer.

RetroFresh, October 2000

With apartheid in full swing and the suppression of all cross cultural activity at its most intense the turn of the '70s was a very difficult time for the emerging "underground" bands. Hawk were among the first of these groups to embrace African culture as part of their musical heritage and created an unique fusion of acoustic folk, psych-rock, driving Afro percussion and vocals with the long forgotten art of storytelling.

Their classic debut album "African Day", released in 1971, combined all of these elements with one of the most incendiary live performances ever seen before and has not been available on any format since the mid '70s (bar a few dodgy Asian bootlegs). Highly prized by collectors worldwide "African Day" has been digitally transferred from virgin vinyl (the original tape masters were destroyed in the '70s) and remastered by band aficionado Peter Pearlson and features all the original songs including the 17 minute epic title track and a stunning Afro cover of the Beatles 'Here Comes The Sun'.

There are also some bonus live tracks (courtesy of David Marks's 3rd Ear Music), rare photos and memorabilia, interviews with the original members and an essay on the life and times of Hawk by noted music journalist Owen Coetzer.

Kindly licensed to RetroFresh by EMI South Africa.

Hawk emerged as an early pioneer of cross-cultural fusion, contemporary with Osibisa's Caribbean-Ghanaian hybrid and preceding Johnny Clegg’s celebrated work with Juluka. Blending classical, folk, jazz, progressive rock and traditional African styles, they created a sound that was uniquely their own.

The 17-minute title track is African story-telling at it's finest.

'Here Comes The Sun', a cover of the George Harrison-penned Beatles classic, was number 78 in the

LM Radio top hits of 1972.

The epic "African Day" was re-recorded in 1972 with some changes, and released on "Africa She Too Can Cry".

Thanks to Neil Daya from Vibes, N1 City, Cape Town for the loan of the original LP.

Additional info supplied by Dave Malherbe (Braam's brother), May 1999.

African Day

Based on the 1973 version of the "African Day" suite released on Africa She Too Can Cry, I have created these sub-sections for the 1971 African Day suite, with appropriate names.

Brian Currin, February 2023

- Introduction

- African Sun

- Strike The Demon Down

- Hunt

- Bulala!

- Nglovu Ephili

- Rejoice!

- Sunset (reprise of coda from Nglovu Ephili)